Reliable event delivery in Apache Kafka based on retry and DLQ

Any complex information system may break at some point and this is why you need to have a plan for when something goes wrong while working with one. If you are lucky, the system you have chosen will provide you with ready-made solutions to deal with emergencies but if you are unfortunate enough to have ended up working with Kafka you will have to find other ways to fix problems. In this blog post you will learn why there is no DLQ (Dead Letter Queue) in Kafka and how to handle a situation that calls for such a mechanism.

Why is there no DLQ in Kafka?

Most popular queueing systems such as RabbitMQ or ActiveMQ have built-in systems responsible for reliable message delivery. So why doesn’t Kafka offer one? The answer to this question is closely related to one of the architectural patterns underlying Kafka: dumb broker / smart consumer. This pattern boils down to the burden of logic associated with handling readings being shifted to the consumer. The consequence of this approach is the lack of a ready-made solution that can help the consumer in case of a problem during message processing. The broker is only interested in one piece of information: the position at which the consumer has committed an offset. Of course, you can always say that in this situation you should choose the right tool for the problem and use a queuing system with such support, however, you do not always have the freedom to implement multiple solutions in one system. If, like me, you have chosen Kafka as your event logging engine, then in case of the described problem you have to deal with it on your own and program it accordingly.

How to deal with errors?

Imagine a situation in which the event handling process involves communication with an external system. You have to decide how the consumer should behave when the external system responds in a different way than expected, or worse - does not respond at all. There are many strategies for handling such a situation. I have chosen four for the purpose of this article.

Lack of error handling

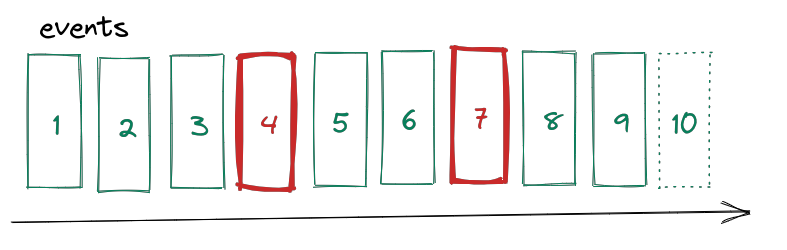

A very popular and frequently used strategy for handling emergencies is lack of response, which all programmers of the world have surely faced. In the figure above, the rectangles denote consecutive messages in the topic. When a consumer encounters a problem processing the offset 4 message, it ignores it and moves on to the next one. Although this approach seems like a not very sensible solution, there are situations where losing some messages does not carry any risk. As an example, consider any solution that stores and analyzes user behavior in an application. Since the task of such a system is to collect statistical data, the loss of single events will not significantly affect the results. However, it is important to have effective monitoring which can detect a situation when the loss of messages exceeds some arbitrarily determined level.

Infinite retry

When you can’t afford to lose messages, the simplest approach is to retry until the delivery succeeds. The obvious consequence is the so-called world stopping, where no further messages will be processed until the error is fixed or the external system is unblocked. Such a solution is necessary if you want to keep the order of processing events in the system. In this scenario, having constant monitoring is even more important.

Finite retry at the point of an error

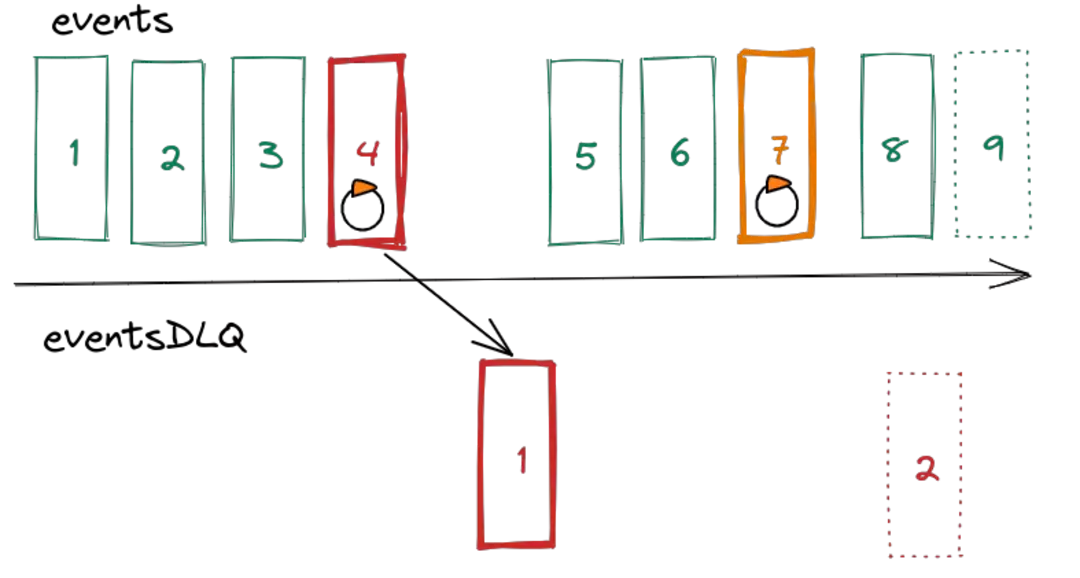

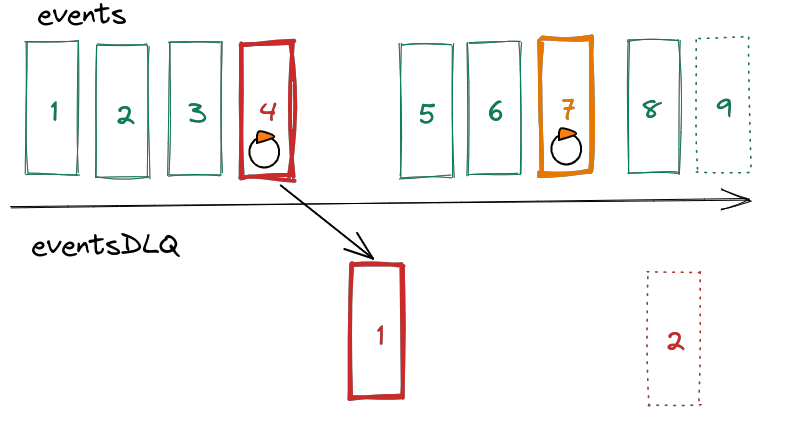

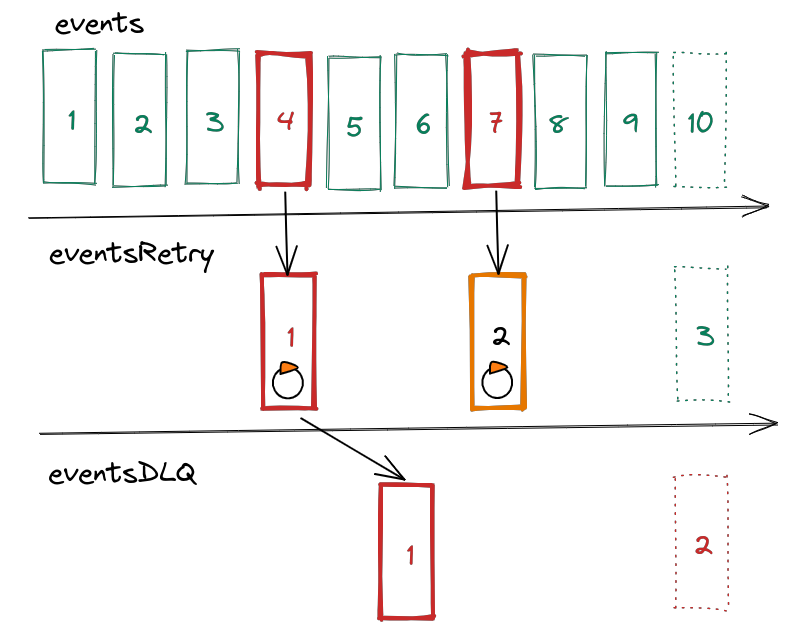

The strategies discussed so far preserve the processing order of events. This is extremely important when events are interdependent and the consistency of your system relies on the order of processing. However, events do not always have this property and not having to preserve the order opens up new possibilities. Imagine what happens when you loosen the requirement for absolute sequentiality a bit. Let’s assume that you keep retrying for a while, because statistics and experience tell you that 99% of problems with message processing are temporary and resolve themselves after some time. Additionally, you copy messages that failed to process to a separate topic treated as DLQ. As a result you have immediately identified problematic messages and you can run a separate consumer group on them. The problematic message 4 stops processing for a moment and then is copied to the topic of broken DLQ events. On the other hand, message 7 is only retried for a short time and after it succeeds, processing is resumed. But why are messages copied and not moved? The answer is very simple - they cannot be moved. This is due to another architectural foundation of Kafka, namely topic immutability. No matter what the cause of the error was, the message will be stored forever. There are ways to deal with this issue and we will come back to this later.

Finite retry on a separate topic

We hereby come to our final solution. Since there is a separate topic for broken messages, it might be a good idea to introduce another one, where duplication takes place. In this model, you loosen the necessity of keeping the order even more, but you get the possibility of uninterrupted processing of the main topic in return. Consequently, you do not stop the world, and the messages are cascaded first to the topic of the retried messages, and in case of failure - to the topic DLQ. Theoretically we should call it DLT, but let’s stick to the acronym DLQ, as it is well associated with this kind of technique. All four of the described options for dealing with an emergency apply to the system that this blog post is concerned with. The challenge is to match the appropriate method to the nature of the data being processed in the topic. It is also worth noting that one should learn from the greatest and that the last two models are heavily inspired by the way Kafka is used by Uber in their systems.

Event tracking

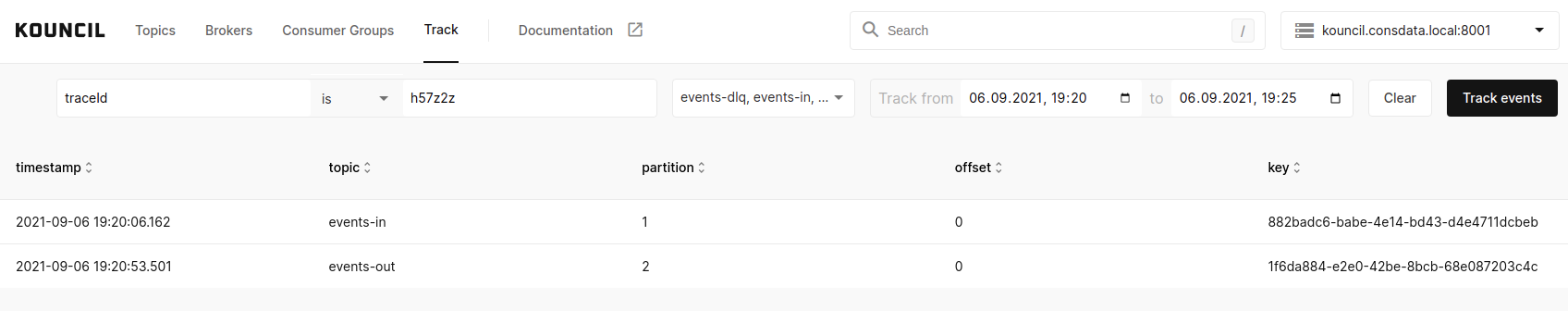

Whatever solution you choose, one thing is for sure: you need a tool that will allow you to track and see how events behave on topics. Kouncil (demo), which we have been developing for some time now, fits especially well in a situation involving the strategy with the retry topic and DLQ. Using track view and having a correlating identifier, you can quickly verify the event processing path. For example, you know that the event with the identifier h57z2z has been correctly processed, i.e. has passed through the events-in and events-out topics, which can be seen in the screenshot below.

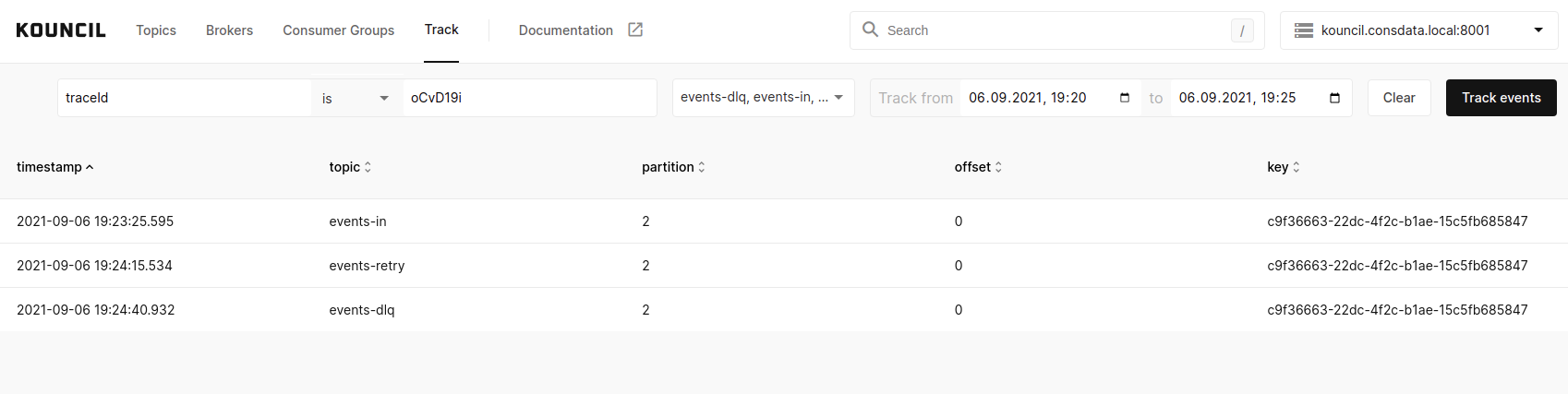

It may happen that you get a notification regarding non-delivery of a message with identifier oCvD19i . A quick glance allows you to confirm that the event first went to the topic for a retry, and eventually landed in DLQ.

You can read more about event tracking in Marcin Mergo’s article Event Tracking - finding a needle in a haystack

DLQ and consumer groups

One more important aspect remains, i.e. how to implement this solution when multiple consumer groups are involved. At first glance it might seem that, similarly to RabbitMQ, the retry topic and DLQ are closely related to the main topic but nothing could be further from the truth. The concept of consumer groups running in Kafka on the same topic but having a different implementation generates the need for the retry mechanism to be tied to a specific group. In particular, different groups may have different paging and error handling logic. The situation becomes even more complicated when consumer groups are dependent on each other in some way. One group may depend on whether another group has correctly processed a given message. In such a case, you have to carefully adjust the retry and error handling mechanisms so that the consistency of message processing is maintained.

Cleanup

Finally, let’s address the problem of data redundancy resulting from messages being copied between topics. In the case of the main topic, every message that eventually made it to the DLQ is considered corrupted. If it is possible to reprocess the message stream in your application, you need to handle this situation somehow. There are at least two solutions:

- A log of corrupted messages, which can be built automatically based on the messages going to the DLQ. It consists of the offsets of messages from the main topic. During reprocessing the consumer, aware of the log, ignores all messages marked in it.

- Compacting a topic - I mentioned that there is no way of changing or deleting messages from a topic. There is an exception to the above rule - the mechanism of compacting a topic. In a nutshell, it works this way: the broker runs a recurring task which browses the topic, collects messages with the same key and leaves only the newest messages. The trick is to insert into the stream a message with the same key as the corrupted one, but with empty content. The consumer must be prepared beforehand to handle such messages. Both techniques can be used at the same time, but it must be remembered that the offsets of compacted messages will disappear irretrievably from the topic.

Topic retry contains messages that have no value after processing, so in this case it is enough to configure retention, i.e. message lifetime. You just have to remember that retention should not be shorter than the longest possible processing time of a single message.

Topic DLQ should contain messages until they are diagnosed and the system is corrected. As this time is not easy to determine, retention is not an option. Hence the trick with date-based keys. If you consider incidents from a certain date to have been resolved, enter an empty message into DLQ with a key in the form of the date, and all messages will be removed from DLQ at the next compacting session.

Summary

I hope that I managed to show on this simple example that an iterative approach to the problem can lead to interesting and effective solutions.

Translation by Piotr Żurawski-

SENIOR FULLSTACK DEVELOPER (JAVA + ANGULAR) Poznań (hybrydowo) lub zdalnie UoP 14 900 - 20 590 PLN brutto

B2B 19 680 - 27 220 PLN netto -

REGULAR FULLSTACK DEVELOPER (JAVA + ANGULAR) Poznań (hybrydowo) lub zdalnie UoP 11 300 - 15 900 PLN brutto

B2B 14 950 - 21 000 PLN netto -

ZOBACZ WSZYSTKIE OGŁOSZENIA

technical

newsletter

-

SENIOR FULLSTACK DEVELOPER (JAVA + ANGULAR) Poznań (hybrydowo) lub zdalnie UoP 14 900 - 20 590 PLN brutto

B2B 19 680 - 27 220 PLN netto -

REGULAR FULLSTACK DEVELOPER (JAVA + ANGULAR) Poznań (hybrydowo) lub zdalnie UoP 11 300 - 15 900 PLN brutto

B2B 14 950 - 21 000 PLN netto -

ZOBACZ WSZYSTKIE OGŁOSZENIA